07 Dec 2023

Introduction #

Although molecular dynamics (MD) has a rightful reputation for requiring long computation times, computationalists spend the longest time setting up a computation. At the beginning of Summer 2023, it took me a week to have any working simulation. I first began using the code that a group member gave me. Ultimately, I decided it would be best to start from scratch. In the process, I learned of the inner workings of AMBER14 (or just Amber). My most valuable finding is that polarizability affects how an aerosol solvates sulfur dioxide.

In the first week of working, I constructed a box of water with a vacuum. It’s important to ensure your simulation is equilibrated, so I wrote some code to quickly take the energy over time and produce a graph on the supercomputer. After testing many configurations, I found that running simulations with one node rather than the maximum number of nodes was the fastest. Here, I refactored the code rather than having all simulation files in the root of a single directory.

Part of MD is ensuring your simulation is accurate enough for your goals. This means using the proper forces and simulating the correct molecules. I wanted to investigate how we know about secondary organic aerosols (SOAs) in the first place. I reviewed the literature on atmospheric chamber studies. I specifically looked at the instruments used in the analysis of SOAs. Unsurprisingly, I found the conclusions of previous authors to be correct and trustworthy.

Ansatz #

Our approach to atmospheric chemistry was simulating the interface of a hypothetical pure water aerosol and its interaction with SO2 and sulfate. Gaseous sulfuric acid arises from the photo-oxidation of SO2. H2SO4 is a powerful nucleating agent. In some cases, it is responsible for most nucleation events. H2SO4 and SO2 are highly soluble in water, so we predicted that SO2 would prefer the bulk solution. I made a box of water in Amber with periodic boundary conditions, about 24Å in length. The box was equilibrated at NPT. Then, the z-axis was expanded to about 100Å. An SO2 molecule, and later sulfate, was placed in the vacuum where it would have minimal interactions with water. Later, it was found that sulfate interacts with water at this distance. The long box was equilibrated with NVT while the SO2 was restrained in position using a restraint force. After equilibration, SO2 was accelerated towards the interface.

Code #

Each working simulation I produced became a checkpoint, and I wrote code on the supercomputer to save a complete backup of the simulation on my desktop. Each backup was saved with a UUID, and identified by a CSV file, which functions as metadata, including the time of backup and a short description. Also, I began a GitHub repository to back up my most up-to-date version of the simulation, along with detailed documentation on setting up the simulation.

Since there are so many parameters to tweak in Amber, I spent a lot of time finding out what each of them does. Over the summer, I kept getting errors when running parallelized simulations. Amber divides the simulation box into slabs for each processor and allocates a certain number of atoms to each slab based on the average density of the simulation box. When too many atoms are in one slab, the simulation stops, resulting in a “non-homogeneous” error. Although large variations in density are uncommon for biological systems, it’s what we want in ours. I eventually realized that Amber was slicing the box into slabs along the xy-plane, so some slabs had water, and others had a vacuum, hence the non-homogeneous error. It only took changing my longest dimension from the z-dimension to the x-dimension to fix the error.

Experimentation #

Around this time, I experimented with constant surface tension calculations, but eventually found it too cumbersome and impossible to equilibrate with constant volume. This is particularly detrimental to the equilibration step after adding SO2. With atoms of nitrogen present, simulating the atmosphere, the box expands to infinity, crashing the run. Without any gas present, the NPγT simulation shrinks such that there is no vacuum.

Early in the Fall of 2023, I was interested in how long sulfur dioxide would spend on the interface. I wrote a lot of code to quantify where the SO2 was relative to the interface. I created a method using the closest water molecules calculated with cpptraj. A bounding box algorithm showed nearly identical results, so I used the x-axis (formerly z-axis) coordinate as a proxy for height above the interface. I also wrote code to quantify how long the SO2 spent in each of the three phases once it arrived at the interface. For some time, it seemed like SO2 would not stay on the interface or go into bulk, counter to what you would expect from a water-soluble molecule. After about a week, I realized I hadn’t added the partial charges to SO2, so it was effectively a non-polar molecule.

We were also interested in what other factors could affect how long SO2 spends on the interface, so I produced more simulations altering the angle of entry and velocity of SO2. With no surprise, such variables had no effect. This was the state of my research when the Fall ACS 2023 conference arrived. Immediately after ACS, I began work on the next variable, polarizability.

Results #

In one study, researchers found that sulfate prefers the center of the aerosol, counter to my results which showed sulfate near the surface. There were two important differences:

- I simulated a slab of water, not a round aerosol.

- They did not simulate with polarizability.

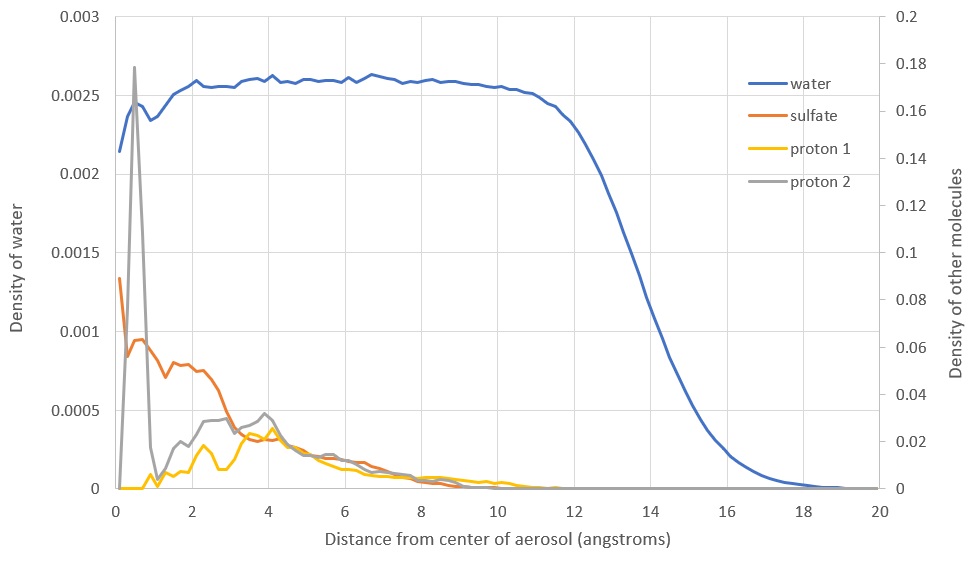

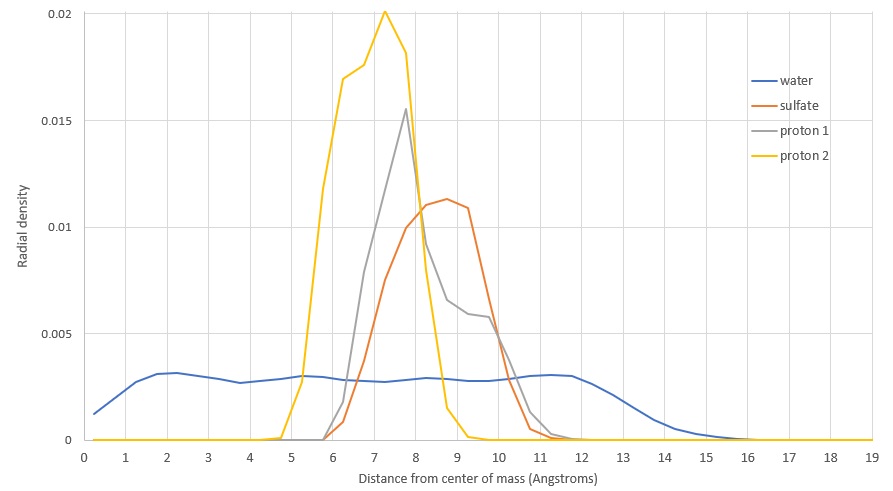

I quickly set up a new simulation with as similar parameters as possible. After toggling the polarizable forcefield, I produced two radial density distribution functions for sulfate in the aerosol. Without polarizability, I got very similar results to the study mentioned. With polarizability, sulfate preferred to be closer to the edge.

Future Work #

The goal now is to determine how much polarizability effects different molecules. I’m also interested in describing polarizability optimization mathematically. The Van der Waals force in Amber already partially accounts for such interactions, which effectively lowers what polarizability values you need to get accurate results.